24 KiB

El Arte del Terminal

- Meta

- Fundamentos

- De uso diario

- Procesamieto de archivos y datos

- Depuración del sistema

- One-liners

- Obscuro pero útil

- Más recursos

- Advertencia

Fluidez en el terminal es una destreza a menudo abandonada y considerada arcaica, pero esta mejora s flexibilidad y productividad como ingeniero en ambas formas obvia y sutil. Esta es una selección de notas y consejos al uar el terminal que encontré útil cuando trabajó en Linux. Algunos consejos son elementales, y algunos bastante específico, sofisiticados, o oscuros. Esta página no es larga, pero si usa y and recuerda todos los puntos aquí, ustedes saben un montón.

Gran parte esta originally appeared en Quora, pero debido al interés mostrado ahí, parece que vale la pena usar Github, donde las personas con mayor talento que facílmente sugerir mejoras. Si yo vez un error o algo que podría ser mejor, por favor, cree un issue o PR! (Por supuesto revise la sección meta de PRs/issues primero.)

Meta

Alcance:

- Esta guía es para ambos el principiante y el experimentado. Los objetivos son diversidad (todo importa), especificidad (dar ejemplos concretos del caso más común), y concisión (evitar cosas que no son esenciales o insignificantes que puedas buscar facilmente en otro lugar). Cada consejo es esencial en alguna situación o significativamente ahorra tiempo comparada con otras alternativas.

- Esta escrito para Linux. Mucho pero no todos los puntos se aplican igualmente para MacOS (o incluso Cygwin).

- Se enficá en Bash interactivo, Aunque muchos de los consejos se aplican para otros shells y al Bash scripting por lo general.

- Esta incluye ambos comandos "estándar" Unix commands así como aquellos que requiren la instalación especial de in paquete -- siempre que sea suficientemente importante para ameritar su inclusión.

Notas:

- Para mantener esto en una página, el contenido esta incluido implicitamente por referencia. Tú eres suficientemente inteligente para ver profundamente los detalles en otros lugares, cuando conoces la idea o comando command en Google. Usar

apt-get/yum/dnf/pacman/pip/brew(según proceda) para instalar los nuevos programas. - Usar Explainshell para obtener detalles de ayuda sobre que comandos, options, pipes, etc.

Fundamentos

-

Aprenda conocimiento básicos de Bash. De hecho, escriba

man bashy al menos echelé un vistazo a todo la cosa; Es bastante fácil de seguir y no es tan largo. Alternar entre shells puede ser agradable, pero Bash es poderoso y siempre esta disponible (Por conocimiento solo zsh, fish, etc., aunque resulte tentador en tu propia laptop, los restringe en muchas situaciones, tales como el uso de servidores existentes). -

Aprenda almenos un editor de texto bien. Idealmente Vim (

vi), como no hay realmente una competencia para la edción aleatorea en un terminal (incluso si usted usa Emacs, un gran IDE, o un editor alternativo (hipster) moderno la mayor parte del tiempo). -

Conozca como leer la documentation con

man(Para curiosos,man manlista las secciones enumeradas, ej. 1 es comandos "regulares", 5 son archivos/convenciones, y 8 are para administración). En en las páginas de manapropos. Conozca que alguno de los comandos no son ejecutables, paro son Bash builtins, y que ouede obtener ayuda sobre ellos conhelpyhelp -d. -

Aprenda sobre redirección de salida y entrada

>y<and pipes utilizando|. Aprenda sobre stdout y stderr. -

Aprenda sobre expansión de archivos glob con

*(y tal vez?y{...}) y quoting y la diferencia entre doble"y simple'quotes. (Ver mas en expansión variable más abajo.) -

Familiarizate con administración de trabajo en Bash:

&, ctrl-z, ctrl-c,jobs,fg,bg,kill, etc. -

Conoce

ssh, y lo básico de authenticacion sin password, viassh-agent,ssh-add, etc. -

Adminisración de archivos básica:

lsyls -l(en particular, aprenda el significado de cada columna inls -l),less,head,tailytail -f(o incluso mejor,less +F),lnyln -s(aprenda las diferencias y ventajas entre hard y soft links),chown,chmod,du(para un rápido resumen del uso del disco:du -sk *). Para administración de filesystem,df,mount,fdisk,mkfs,lsblk. -

Administración de redes básico:

ipoifconfig,dig. -

Conozca expresiones regulares bien, y varias banderas (flags) para

grep/egrep. El-i,-o,-A, y-Bson opciones dignas de ser conocidas. -

Aprenda el uso de

apt-get,yum,dnfopacman(dependiendo de la dismtribución "distro") para buscar e instalar paquetes. Y asegurate que tienespippara instalar la herramienta de linea de comando basada en Python (un poco más abajo esta super fácil para instalar víapip).

De uso diario

-

En Bash, se usa Tab para completar los argumentos y ctrl-r para buscar, a través, del historial de comandos.

-

En Bash, se usa ctrl-w para borrar la última palabra, y ctrl-u para borrar to delete todo el camino hasta el inicio de la línea. Se usa alt-b y alt-f para moverse entre letras, ctrl-k para eliminar hasta el final de la línea, ctrl-l para limpiar la panatalla. Ver

man readlinepara todos los atajos de teclado por defecto en Bash. Son una gran cantidad. Por ejemplo alt-. cicla, a través, de los comandos previos, y alt-* expande un glob. -

Alternativamente, si tu amas los atajos de teclado vi-style, usa

set -o vi. -

Para ver los últimos comandos,

history. También existen abreviaciones, tales como,!$(último argumento) y!!último comando, auque sin facílmente remplazados con ctrl-r y alt-.. -

Para volver al diretorio de trabajo previo:

cd - -

Si estas a mitad de camino de escritura de un comando pero cambias de opinión, presiona alt-# para agregar un

#al princio y lo agrega como comantario (o usar ctrl-a, #, enter). Para que puedas entonces regresar a este luego vía comando historyYou can then return to it later via command history. -

Se usaxargs(orparallel). Este es muy poderoso. Nota: tú puedes controlar muchos items por ejecutados por línea (-L) tamabién, es conocido como paralelismo (-P). Si no estas seguro, esto puede ser la cosa correcta, usaxargs echoprimero. También,-I{}` es comodo. Ejemplos:

find . -name '*.py' | xargs grep some_function

cat hosts | xargs -I{} ssh root@{} hostname

-

pstree -pes útil para mostrar el árbol de procesos. -

Se usa

pgrepypkillpara encontrar o señalar procesos por su nombre (-fes de mucha ayuda). -

Conocer varias señales que puedes enviar a los procesos. Por ejemplo, para suspender un proceso, usa

kill -STOP [pid]. Para la lista completa, consultarman 7 signal -

Usa

nohupodisownsi quieres mantener un proceso de fondo corriendo para siempre. -

Verifica que procesos esta escuchando via

netstat -lntposs -plat(para TCP; agrega-upara UDP). -

Consulta también

lsofpara abrir sockets y archivos. -

En Bash scripts, usa

set -xpara depurar la salida. Utiliza el modo estricto cuando se posible. Utilizaset -epara abortar en errores. Utilizaset -o pipefailtambién, para ser estrictos sobre los errores (auque este tema es un poco delicado). Para scripts más complejos, también se puede utilizartrap. -

En Bash scripts, subshells (escritos con parentesís) son maneras convenientes para agrupar los comandos. Un ejemplo común es para moverse temporalment hacia un diferente directorio de trabajo, Ej.

# do something in current dir

(cd /some/other/dir && other-command)

# continue in original dir

-

En Bash, considere que hay muchas formas de expansión de vaiables. Verificar la existencia de una variable:

${name:?error message}. Por ejemplo, si un script Bash requiere un único argumento, solo escribainput_file=${1:?usage: $0 input_file}. Expansión arítmetica:i=$(( (i + 1) % 5 )). Secuencias:{1..10}. Reducción de strings:${var%suffix}y${var#prefix}. Por ejemplo sivar=foo.pdf, entoncesecho ${var%.pdf}.txtimprimefoo.txt. -

La salida de un comando puede ser tratado como un archivo, via

<(some command). Por ejemplo, compare local/etc/hostscon uno remoto:

diff /etc/hosts <(ssh somehost cat /etc/hosts)

-

Conocer acerca "here documents" en Bash, así también

cat <<EOF .... -

En Bash, redireccionar ambas salida estandar y error estandar, via:

some-command >logfile 2>&1. Frecuentemente, para garantizar que un comando no haya dejado abierto un archivo para controlar la entrada estandar, vinculado al terminal en el que te encuentras, esta también como buena practica puedes agregar</dev/null. -

Usa

man asciipara una buena tabla ASCII, con valores hexadecimal y decimales. Para información de codificación general,man unicode,man utf-8, yman latin1son de utilidad. -

Usa

screenotmuxpara multiplexar la pantalla, espcialmente útil en sessiones ss remotas y para desconectar y reconectar a una sessión. Una alternativa más minimalista para persistencia de la sessión solo seríadtach. -

En ssh, conocer como hacer un port tunnel con

-Lo-D(y de vez en cuando-R) es útil, Ej. para acceder sitio web desde un servidor remoto. -

esto puede ser útil para hacer algunas optimizaciones para su configuración ssh; por ejemplo, Este,

~/.ssh/configcontiene la configuracion para evitar desxonexiones en ciertos entornos de red, usar comprensión (la cual es muy útil con scp sobre conexiones con un ancho de banda pequeño), y multiplexar canales para el mismo servidor con un archivo de control local:

TCPKeepAlive=yes

ServerAliveInterval=15

ServerAliveCountMax=6

Compression=yes

ControlMaster auto

ControlPath /tmp/%r@%h:%p

ControlPersist yes

-

Unas pocas otras opciones relevantes para ssh son are sensitivas a la seguridad y deben ser activadas con cuidado, Ej. "per subnet", "host" o "in trusted networks:

StrictHostKeyChecking=no,ForwardAgent=yes -

Para optener permiso sobre un archivo en forma octal form, el cual es útil para la configuración del sistema pero no disponible con

lsy fácil de estropear, usando algo como

stat -c '%A %a %n' /etc/timezone

-

Para selección interactiva de valores desde la salida de otro comando, usa

percol. -

Para la interacción con archivos basados en la salida de otro comando (como

git), usafpp(PathPicker). -

Para un servidor web sencillo para todos los archivos en el directorio actual (y subdirectorios), disponible para cualquiera en tu red, usa:

python -m SimpleHTTPServer 7777(para el puerto 7777 y Python 2) ypython -m http.server 7777(para 7777 y Python 3).

Processing files and data

-

To locate a file by name in the current directory,

find . -iname '*something*'(or similar). To find a file anywhere by name, uselocate something(but bear in mindupdatedbmay not have indexed recently created files). -

For general searching through source or data files (more advanced than

grep -r), useag. -

To convert HTML to text:

lynx -dump -stdin -

For Markdown, HTML, and all kinds of document conversion, try

pandoc. -

If you must handle XML,

xmlstarletis old but good. -

For JSON, use

jq. -

For Excel or CSV files, csvkit provides

in2csv,csvcut,csvjoin,csvgrep, etc. -

For Amazon S3,

s3cmdis convenient ands4cmdis faster. Amazon'sawsis essential for other AWS-related tasks. -

Know about

sortanduniq, including uniq's-uand-doptions -- see one-liners below. -

Know about

cut,paste, andjointo manipulate text files. Many people usecutbut forget aboutjoin. -

Know about

wcto count newlines (-l), characters (-m), words (-w) and bytes (-c). -

Know about

teeto copy from stdin to a file and also to stdout, as inls -al | tee file.txt. -

Know that locale affects a lot of command line tools in subtle ways, including sorting order (collation) and performance. Most Linux installations will set

LANGor other locale variables to a local setting like US English. But be aware sorting will change if you change locale. And know i18n routines can make sort or other commands run many times slower. In some situations (such as the set operations or uniqueness operations below) you can safely ignore slow i18n routines entirely and use traditional byte-based sort order, usingexport LC_ALL=C. -

Know basic

awkandsedfor simple data munging. For example, summing all numbers in the third column of a text file:awk '{ x += $3 } END { print x }'. This is probably 3X faster and 3X shorter than equivalent Python. -

To replace all occurrences of a string in place, in one or more files:

perl -pi.bak -e 's/old-string/new-string/g' my-files-*.txt

- To rename many files at once according to a pattern, use

rename. For complex renames,reprenmay help.

# Recover backup files foo.bak -> foo:

rename 's/\.bak$//' *.bak

# Full rename of filenames, directories, and contents foo -> bar:

repren --full --preserve-case --from foo --to bar .

-

Use

shufto shuffle or select random lines from a file. -

Know

sort's options. Know how keys work (-tand-k). In particular, watch out that you need to write-k1,1to sort by only the first field;-k1means sort according to the whole line. -

Stable sort (

sort -s) can be useful. For example, to sort first by field 2, then secondarily by field 1, you can usesort -k1,1 | sort -s -k2,2 -

If you ever need to write a tab literal in a command line in Bash (e.g. for the -t argument to sort), press ctrl-v [Tab] or write

$'\t'(the latter is better as you can copy/paste it). -

The standard tools for patching source code are

diffandpatch. See alsodiffstatfor summary statistics of a diff. Notediff -rworks for entire directories. Usediff -r tree1 tree2 | diffstatfor a summary of changes. -

For binary files, use

hdfor simple hex dumps andbvifor binary editing. -

Also for binary files,

strings(plusgrep, etc.) lets you find bits of text. -

For binary diffs (delta compression), use

xdelta3. -

To convert text encodings, try

iconv. Oruconvfor more advanced use; it supports some advanced Unicode things. For example, this command lowercases and removes all accents (by expanding and dropping them):

uconv -f utf-8 -t utf-8 -x '::Any-Lower; ::Any-NFD; [:Nonspacing Mark:] >; ::Any-NFC; ' < input.txt > output.txt

-

To split files into pieces, see

split(to split by size) andcsplit(to split by a pattern). -

Use

zless,zmore,zcat, andzgrepto operate on compressed files.

System debugging

-

For web debugging,

curlandcurl -Iare handy, or theirwgetequivalents, or the more modernhttpie. -

To know disk/cpu/network status, use

iostat,netstat,top(or the betterhtop), and (especially)dstat. Good for getting a quick idea of what's happening on a system. -

For a more in-depth system overview, use

glances. It presents you with several system level statistics in one terminal window. Very helpful for quickly checking on various subsystems. -

To know memory status, run and understand the output of

freeandvmstat. In particular, be aware the "cached" value is memory held by the Linux kernel as file cache, so effectively counts toward the "free" value. -

Java system debugging is a different kettle of fish, but a simple trick on Oracle's and some other JVMs is that you can run

kill -3 <pid>and a full stack trace and heap summary (including generational garbage collection details, which can be highly informative) will be dumped to stderr/logs. -

Use

mtras a better traceroute, to identify network issues. -

For looking at why a disk is full,

ncdusaves time over the usual commands likedu -sh *. -

To find which socket or process is using bandwidth, try

iftopornethogs. -

The

abtool (comes with Apache) is helpful for quick-and-dirty checking of web server performance. For more complex load testing, trysiege. -

For more serious network debugging,

wireshark,tshark, orngrep. -

Know about

straceandltrace. These can be helpful if a program is failing, hanging, or crashing, and you don't know why, or if you want to get a general idea of performance. Note the profiling option (-c), and the ability to attach to a running process (-p). -

Know about

lddto check shared libraries etc. -

Know how to connect to a running process with

gdband get its stack traces. -

Use

/proc. It's amazingly helpful sometimes when debugging live problems. Examples:/proc/cpuinfo,/proc/xxx/cwd,/proc/xxx/exe,/proc/xxx/fd/,/proc/xxx/smaps. -

When debugging why something went wrong in the past,

sarcan be very helpful. It shows historic statistics on CPU, memory, network, etc. -

For deeper systems and performance analyses, look at

stap(SystemTap),perf, andsysdig. -

Confirm what Linux distribution you're using (works on most distros):

lsb_release -a -

Use

dmesgwhenever something's acting really funny (it could be hardware or driver issues).

One-liners

A few examples of piecing together commands:

- It is remarkably helpful sometimes that you can do set intersection, union, and difference of text files via

sort/uniq. Supposeaandbare text files that are already uniqued. This is fast, and works on files of arbitrary size, up to many gigabytes. (Sort is not limited by memory, though you may need to use the-Toption if/tmpis on a small root partition.) See also the note aboutLC_ALLabove andsort's-uoption (left out for clarity below).

cat a b | sort | uniq > c # c is a union b

cat a b | sort | uniq -d > c # c is a intersect b

cat a b b | sort | uniq -u > c # c is set difference a - b

-

Use

grep . *to visually examine all contents of all files in a directory, e.g. for directories filled with config settings, like/sys,/proc,/etc. -

Summing all numbers in the third column of a text file (this is probably 3X faster and 3X less code than equivalent Python):

awk '{ x += $3 } END { print x }' myfile

- If want to see sizes/dates on a tree of files, this is like a recursive

ls -lbut is easier to read thanls -lR:

find . -type f -ls

- Use

xargsorparallelwhenever you can. Note you can control how many items execute per line (-L) as well as parallelism (-P). If you're not sure if it'll do the right thing, use xargs echo first. Also,-I{}is handy. Examples:

find . -name '*.py' | xargs grep some_function

cat hosts | xargs -I{} ssh root@{} hostname

- Say you have a text file, like a web server log, and a certain value that appears on some lines, such as an

acct_idparameter that is present in the URL. If you want a tally of how many requests for eachacct_id:

cat access.log | egrep -o 'acct_id=[0-9]+' | cut -d= -f2 | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn

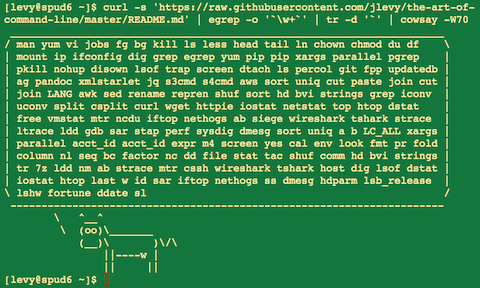

- Run this function to get a random tip from this document (parses Markdown and extracts an item):

function taocl() {

curl -s https://raw.githubusercontent.com/jlevy/the-art-of-command-line/master/README.md |

pandoc -f markdown -t html |

xmlstarlet fo --html --dropdtd |

xmlstarlet sel -t -v "(html/body/ul/li[count(p)>0])[$RANDOM mod last()+1]" |

xmlstarlet unesc | fmt -80

}

Obscure but useful

-

expr: perform arithmetic or boolean operations or evaluate regular expressions -

m4: simple macro processor -

yes: print a string a lot -

cal: nice calendar -

env: run a command (useful in scripts) -

printenv: print out environment variables (useful in debugging and scripts) -

look: find English words (or lines in a file) beginning with a string -

cutandpasteandjoin: data manipulation -

fmt: format text paragraphs -

pr: format text into pages/columns -

fold: wrap lines of text -

column: format text into columns or tables -

expandandunexpand: convert between tabs and spaces -

nl: add line numbers -

seq: print numbers -

bc: calculator -

factor: factor integers -

gpg: encrypt and sign files -

toe: table of terminfo entries -

nc: network debugging and data transfer -

socat: socket relay and tcp port forwarder (similar tonetcat) -

slurm: network trafic visualization -

dd: moving data between files or devices -

file: identify type of a file -

tree: display directories and subdirectories as a nesting tree; likelsbut recursive -

stat: file info -

tac: print files in reverse -

shuf: random selection of lines from a file -

comm: compare sorted files line by line -

hdandbvi: dump or edit binary files -

strings: extract text from binary files -

tr: character translation or manipulation -

iconvoruconv: conversion for text encodings -

splitandcsplit: splitting files -

units: unit conversions and calculations; converts furlongs per fortnight to twips per blink (see also/usr/share/units/definitions.units) -

7z: high-ratio file compression -

ldd: dynamic library info -

nm: symbols from object files -

ab: benchmarking web servers -

strace: system call debugging -

mtr: better traceroute for network debugging -

cssh: visual concurrent shell -

rsync: sync files and folders over SSH -

wiresharkandtshark: packet capture and network debugging -

ngrep: grep for the network layer -

hostanddig: DNS lookups -

lsof: process file descriptor and socket info -

dstat: useful system stats -

glances: high level, multi-subsystem overview -

iostat: CPU and disk usage stats -

htop: improved version of top -

last: login history -

w: who's logged on -

id: user/group identity info -

sar: historic system stats -

iftopornethogs: network utilization by socket or process -

ss: socket statistics -

dmesg: boot and system error messages -

hdparm: SATA/ATA disk manipulation/performance -

lsb_release: Linux distribution info -

lsblk: List block devices: a tree view of your disks and disk paritions -

lshw: hardware information -

fortune,ddate, andsl: um, well, it depends on whether you consider steam locomotives and Zippy quotations "useful"

More resources

- awesome-shell: A curated list of shell tools and resources.

- Strict mode for writing better shell scripts.

Disclaimer

With the exception of very small tasks, code is written so others can read it. With power comes responsibility. The fact you can do something in Bash doesn't necessarily mean you should! ;)

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licene.